EIZO Interviews Clive Booth

Clive Booth - Designer, Photographer and Filmmaker

In conversation with Mike Owen, Head of Marketing at EIZO UK

Clive Booth is a commercial photographer who has worked for many world famous iconic fashion and luxury brands. He has photographed celebrities around the world and shot films for global names. He is a Canon Ambassador, who is constantly on the lookout for what is new and has recently been working on VR-content. Content to tell immersive stories, content to empower, content to engage but most importantly, Clive creates content in any form, to build emotion in the viewer.

I have known Clive for many years as I was part of the team at Canon Europe that added him to the Canon Ambassador programme; a role which he proudly holds today. In fact, I was lucky enough to be given an incredible print of one of his images when I left Canon and we have kept in touch ever since. So, when I arrived at EIZO I was pleased to discover that Clive was a long-term user and fan. I was excited because I knew from experience that he would become one of our most public cheerleaders.

When I first spoke to Clive about the possibility of doing an interview on behalf of EIZO, I thought I might get the chance to talk to him from his Derbyshire home, so when he offered to come down to our Ascot HQ to conduct the interview in person, I was blown away. For Clive to then inform me that he would be joined by his long-term agent and friend Mark George, I felt really honoured. Mark George has been Clive’s agent since his early days as a photographer and has represented some of the world’s biggest photographers including the legendary Richard Avedon, and he still represents the indomitable spirit, photojournalistic legend and incredible man, Sir Don McCullin. So, for me we are talking about photographic royalty.

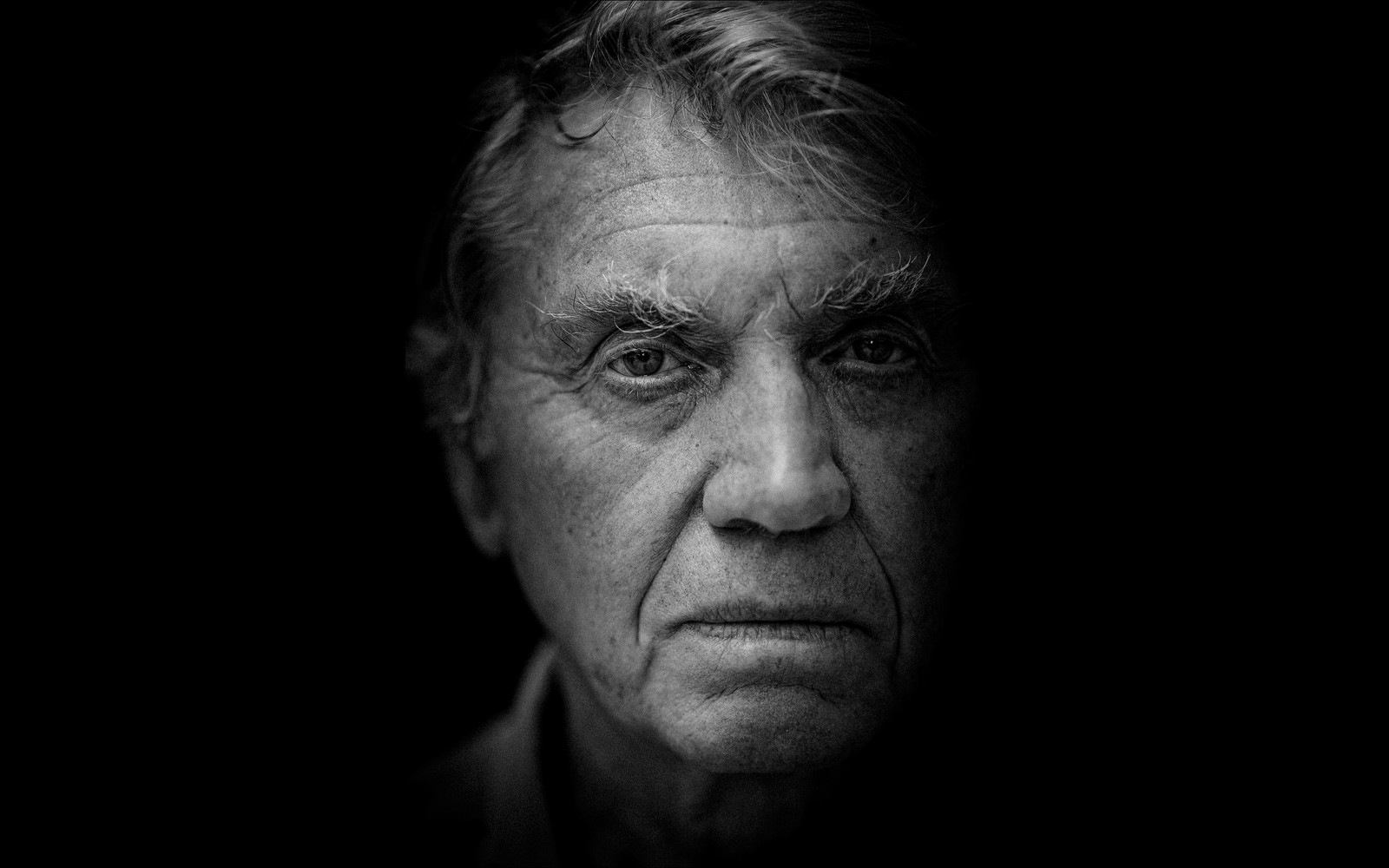

Sir Don McCullin

“Mark George represents both Sir Don McCullin and Clive and this has brought many opportunities for the two to work together, their last collaboration was a film directed by Clive of Don shooting the street people of Kolkata.

Even though I’ve made many films of Don over the years I have only ever shot one portrait that I feel happy with, this one.”

Emotional intelligence in photography

In interviews I usually go through the pre-amble of getting to know the subject but given the fact that I had known both Clive and Mark, I threw that straight out of the window and it may be apt that I am writing this article (even though it will not be published for a while) during Mental Health Awareness week, given the fact that I was talking to a photographer who is by his own admission an emotional photographer, a photographer who wears his heart on his sleeve, so I jump straight in and ask Clive about how emotion shapes his creativity, he responds “Where do you start? OK, let’s start right here, I’m completely open about this and transparent about this, I’m a very sensitive person, but Mark will tell you this probably the most sensitive photographer you represent.” to which Mark interjects “By A long shot since the beginning, since I started representing (photographers)”, but this response is not said with any hint of negativity, the response is so matter of fact that you can tell that Mark and Clive have had many conversations on this area previously.

Given the very open response I received from Clive on this subject I wanted to delve deeper. Many photographers talk about the ability to connect with their subject, which highlights an ability to communicate and empathise with them, so I wanted to understand whether Clive has always had this ability to empathise with whoever he is photographing, or if this is something he has developed over the years. Clive tells me, “As a kid, I was incredibly sensitive. I mean, I was the kid who would cry when Cat Stevens ‘Morning has Broken’ was played in primary school, I would hide my tears, because I knew the other lads would probably get me in a fight or something. I remember my first day at school, I hid under the car seat, didn’t want to go to school, cried all the way through weeks of school and the only way that the headmaster could stop me crying was to put me in my sister’s class and sit me next to her. All my life I’ve suffered with this, heightened sensitivity, which for want of a better word, you might call anxiety. But I guess it’s a double-edged sword, isn’t it? On the one hand you’re incredibly empathetic, sensitive, but on the other hand, the payback is that you get upset easily. As Mark will tell you, whenever I’ve done a shoot, and I’m thinking back of all the shoots that I’ve done, I remember nearly all of them.”

Karen Gillen

“The A list Scottish model, actor, director in Cannes pre Hollywood, Cannes 2012. Such a huge talent, so beautiful and great fun to work with. As she was about to move to Hollywood I came up with the idea of her peering into the Villas pool as if looking into the future. Reaching out and touching the waters surface was all Karen.”

Remembering a shoot for a photographer is no different to a footballer remembering a match or a sales rep remembering a deal, but what is probably less normal is the post shoot reaction. As Mark elaborates, “Every time he does a shoot I wait for the ‘call’. It comes at the end of the shoot, ‘I don’t have it. I screwed it up here. This is the worst thing I’ve ever done. This is absolutely terrible. I could have done better. This didn’t work. I don’t know why I wasn’t prepared. Look at the results, terrible’. I respond, yes Clive. Then the next day he’s beginning to like these. A week later, this is the best work he’s ever done!”.

Clive shoots back “It’s genuine, that feeling is genuine, I have this terrible need for everything to be perfect and that is probably the worst thing of all. Even beyond the sensitivity, because you are just trying to achieve perfection, you just procrastinate. I’m the world’s greatest procrastinator.” The back and forth between Clive and Mark continues with Mark retorting, “You can’t achieve perfection in photography anyway. You can’t. I don’t know any photographer that doesn’t think I wish I had another two days to do that shot because I could have tuned it in a little bit better. But actually, it is great for photographers to learn when to stop tuning something in and take the picture. You can’t go on forever because it’s just not practical, and there comes a point when you go overkill on a picture, and it looks like they’ve been trying too hard.”

Is Mark, right? Can a picture be too perfect? Can the contents of a picture be overkill? A picture can lack in emotion, a picture can be too sterile, does that stem from the subject or from the photographer or a combination of both? Clive provides his thought on the matter, “You will see it in their work, when a photographer picks the camera up and shoots purely on instinct. I have a theory, that we don’t trust that instinct enough as human beings, and we should. I teach young people, and I talk about learning to trust your instinct. There’s a great book on this called ‘Blink’, from the 90s. It talks about instincts and working with instinct and how we carry a huge amount of information. There’s a great story, that I hope is not an urban myth, because it is so damn good, about Cartier-Bresson. An advertising agency commissioned him to do a shoot. He then spent a week with the art director, just looking at a particular street scene. The art director asked if he was going to take a picture, and he didn’t. He waited and waited then on the last day finally he bought the camera took a handful of pictures that became the great picture for that decisive moment, he observed and absorbed, but the shot itself was instinctive.”

Len Goodman

“A rare editorial shoot for You magazine, I was one of the first photographers outside of the show to be allowed back stage for Strictly Come Dancing. I shot many of the stars but my two favourites were Len Goodman and Bruce Forsyth. Len wasn’t wearing any trousers and I’ll always regret not shooting a wider portal!”

Cameras can freeze time in thousands of a second, but the action of getting ready to be in the right place at the right time, with the camera set exactly right and then pressing the button takes years of practice to be able to do it consistently. Young and inexperienced photographers may be able to do it sometimes, but the experts will be able to do it again and again, because they will have developed that instinctive nature. The instinctive nature of photography is one element alongside the technical requirement of using the camera, but Clive’s ability to observe, emphasise and engage with his subjects really stands out to me. Clive outlines an experience when shooting the famous British actor Terence Stamp, “I want to capture the person, that person’s character. My best example of that was when I met Terence Stamp in a Berwick Street tearoom. It was one of those times in my life when you get this urge that you want to photograph someone, he’s got this shock of white hair, and an incredible face. Many times, you have a fear of being rejected, and I think as human beings, we all suffer from fear of rejection, whatever it might be. I wasn’t there to photograph Terence. I was actually being interviewed by a producer to be represented for directing commercials. So, Terence Stamp was sitting there and he’s talking to people, and I could read from his body language and the way he was talking to people that he was receptive to a conversation.

Terence Stamp

“I met the legendary British movie star in a tea shop in Soho, plucked up the courage to say hello and then persuaded him to come back the next day so I could shoot his portrait.”

Here’s the important point, and this is the point I make to all young people I work with, is that so much of being a creative is not about the camera. It’s not about the technology. It’s about interpersonal skills, particularly if you’re going to be a portrait photographer and work with people. You’ve got to really develop those interpersonal skills, and you’ve got to be able to read people. I approached Terence and had a brief conversation during which he agreed to be photographed.

So, we met at the tea shop the next day and rather than bringing the camera up as a barrier, we first talked about his time working with Tim Burton and Steven Soderbergh. About 40 minutes in, I asked do you mind if I take some pictures, and shall we keep the conversation going. And as we talked, I would bring the camera up, shoot some pictures and then put it down again. We carried on talking and I would take out the camera again. Terance was talking to me, but he was also talking to the lens of the camera.” It becomes clear that something that Clive has in spades is emotional intelligence, which is so important for a photographer who photographs people, and intimate scenes, small groups and events.

Clive starts to explain about a photographer called Jane Bowen, “Jane Bowen was one of the great newspaper photographers. The way she worked was that she would go somewhere where all the other press photographers would turn up and there would be a sea of lenses and cameras. But she never had a camera in sight.” Mark picks up, “Her camera was in a bag, and she always stood at the back. With all the photographers saying, ‘over here, look at the camera’, sort of stuff. And then they’re done, and they all split, and the subject would look up and see this little woman standing there with no camera. The subject would wonder who is this and ask why didn’t she take any pictures? Jane would invariably respond ‘Well, all I was going to get is a picture of the back of heads”. And every time they would ask, ‘Do you want to take some now?’ She always got the shot that won the awards. That approach made her a top photographer; she knew to use the camera after she had made contact.”

Clive continues, “The thing is, what she did there was that the subject she went to photograph had an empathy for her in that situation. Mark jumps in, “and that was when she began shooting.” There is a famous story of when Jane Bowen was shooting The Beatles, she was asked to leave at the end of the shoot, but Ringo Starr insisted she be able to stay, some of these images were used in Jane’s obituary on the Guardian shortly after she passed away in 2014.

Robbie Brown

“Robbie Brown was 9-years old when I shot this portrait and I was there to photograph his dad, Scott, who was an RNLI volunteer. Robbie would keep appearing on a quad bike and try to get my attention. Suddenly, he appeared with a puppy and a lolly. I looked and didn’t say a word, brought my camera up and took this picture. There was something about the composition, his shirt and his lolly, and it was just one of those moments in time. I really empathised with him wanting to be part of it all. Tragically, his dad died four years later of a heart attack, so I often think about Robbie and his dad who became a very good friend of mine, as did his whole family. It’s a picture that has become very important to me.”

Islay Lifeboat

“For several years I have followed the Royal National Lifeboat Institution volunteers of the Hebridean Island of Islay. I’m fascinated by these extraordinary people who put there lives at risk often with young families to save the lives of complete strangers. I used dyptic portraiture to illustrate the volunteers in their day jobs and then in RNLI crew kit.”

RNLI Celebrating the extraordinary commitment of the thousands of volunteers who make it possible

The photographer makes the difference

It feels like Mark and Clive are speaking in one continuous sentence, as Clive provides a little insight into the gear he uses, but you can tell that this train of thought was inspired by the way that Jane Bowen used to work. “I used to just carry 1 camera body and one lens and at the time it was really, really unusual for anyone to shoot in the low light that we were shooting in without flash.” The back and forth continues with Mark joining in with, “getting the pictures that felt that way, was that you always shot in the light and immediately had mood. It was like an oil painting, you know.”

Clive elaborates, “I was shooting f/1.2, and I built a career on shooting shallow focus. In those days, not like now where I’m quite happy for the camera to do it all. I’m not one of these people who has the T-Shirt that says you’re not a photographer until M (Manual mode). When I interviewed Martin Parr for WEX during COVID, I asked him the question, what settings do you have on your camera and he said, “I’m on P (Program mode)”.

I think when I started out if I could have done that, (shot in Program mode) I would, but of course in those days people weren’t doing that. So, I built a career on shooting these really atmospheric lavish party pictures, and then I went on to do backstage. When you’re working backstage, particularly, with someone like Nick Knight, you’ve got ‘A listers’, you’ve got to be completely trusted. I would always wear a dinner jacket, and I’d have a camera body with my 85 mm prime. It was almost like it could shoot round corners, and I built a career on that.

Heston Blumenthall

“I first met the great chef through my work with LVMH and shooting lavish events for Moet and Chandon. He invited me to shoot a book with him but sadly his graphic designers had other ideas. I did shoot a series of portraits, this being my favourite as it’s pure minimalism, In the Fat Ducks development kitchen he always seemed to have a spoon in his hand and I thought that’s the perfect prop.”

Heston Blumenthal Thirty minutes before service and it’s like the opening night

I think Nick had seen something in that work, and he quickly realised he could trust me to be on his set. If I look back now, I lacked confidence. If I had those opportunities now? Oh my God, the portraits I would get now that I didn’t get then, because unlike the Terence Stamp situation, I lacked the courage to ask people to let me photograph them. I think we missed the whole thing about emotion. It is so important when you can empathise with someone. For me at my age and my stage in my career, it’s the legacy. Every picture I take is not just a legacy for me, it’s going to impact the legacy for the person I’m photographing.” The impact of the photograph on the legacy of the subject is a concept that is often overlooked, and as we spoke about this with Hamish Brown in a previous conversation, an image can define a specific period or, in some instances, an entire career of a subject.

If a photograph can create or be part of the legacy of an individual, that raises the question, what part does the photographer play in that legacy? Mark unprompted continues with a theory that I have had since early on in my career within the creative sector, “Photography is a really strange art form, a strange medium, because if you had two photographers, set them standing side by side with the same equipment to take the same picture, they would be different 100% and that is very strange. For years I’ve often thought, how am I going to explain why that is the case? And I can’t give an answer to it, but it’s something very ethereal as something bizarre happens. It proves the point that photography, if it’s good, comes from your soul, from your heart. The difference between these two guys standing there with the same equipment to photograph the same subject, is that there’s one that has evolved with all his experiences, and the other guy has done it a different way. Even if they had similar upbringings, they still have different experiences and that manifests itself when they decide to take the picture because that’s the issue, the difference is the photographer not the equipment.

All of which brings us back to the point of the emotion and emotional intelligence of the photographer and their ability to engage with their subject. Our emotions dictate everything we do, whether it’s a shoot, whether it’s an edit, whether it’s which images somebody buys, it’s because of an emotion, an emotional attachment. I asked Clive how much his emotional state drives his creative work and the creative you have become? Clive tells me, “Definitely, I look to tell a story through pictures. You look at composition, you look at everything. But I knew from an early age that I wanted to be an artist, I didn’t know quite how. Even now, at my age now, I’m still exploring. My latest work, immersive storytelling, the work we’re doing with The Birmingham Royal Ballet to bring neurodivergent young people to live theatre, which they can’t normally do. So, the other important thing for me is meaning in work. Now, that’s an important thing. But the other thing I should say is important is that I’m entirely, completely selfish, so I love to please myself first. I’m not shooting for anybody else, even if it’s a commission, I’m not shooting for anybody else.

Carlos Acosta

“Shooting one of the world’s greatest dancers for Birmingham Royal Ballet and Digital Photographer Magazine. I’d research all the pictures taken of Carlos and wanted to do something different and he didn’t disappoint!”

From pose to print: Clive Booth’s shoot with a ballet superstar

The best commissions are when they are choosing you for the way you look at the world. I have been brought in to do my thing, my selective focus, atmospheric capture, the feeling and capture the emotion of the day. I remember this lady from the client coming over and she literally stroked my back and asked me ‘can you get a flash out?’ She wanted me to shoot pictures like they do for ‘Hello Magazine’, I responded I don’t do that, that’s not what I do. Have a look at what I do. Does any of that look like it was shot with flash? You’re asking me to strip away everything that makes my work me and make it look like everyone else’s. I said I’m not going to do that. So, I think standing true to your own values of who you are and what you are. It’s your integrity. Empathy, sensitivity, emotion are all important, but so is the integrity of what you do and actually holding true to you, to the values of what you do. I’m so selfish when I shoot, but of course on the back of that you take a lot of responsibility and that’s why at the end of a shoot, sometimes I get very depressed. Well, I almost always get depressed because I can’t see it, it’s not good enough for what I want it to be.”

This last point was a Wow! Moment for me. You often hear about post event blues or athletes feeling a loss of identity when they stop competing but for a professional such as Clive to admit that he feels depressed after every shoot? I knew Clive was always engaged with and committed to his shoots, but the fact that he is admitting that he feels depressed at the end of the shoot was a revelation, but the phenomenon of post-performance depression is not new and is becoming more widely acknowledged. As Clive explains, “It’s a big, big deal now, it is seen with dancers and performers and sports people, we know that mental well-being is a big issue generally, particularly in young people. But I absolutely have that sort of post-performance depression without any question, and it takes me a long time, to come back from that. The important thing is that I’m full of energy, passion, drive and enthusiasm. I like to create fun as well, and that’s important. Even though I’m wracked with anxiety and nervousness that does eventually turn into energy that becomes positive.”

Al Worden

“In 1971 he orbited the moon 75 times on one of the most ambitious and complex missions of the entire Apollo Space Program. Al is one of only twenty four human beings to have visited the moon. For someone of my generation Apollo has been both a lifelong inspiration and motivation and to be in the presence of a man who was part of one of the most incredible and ambitious achievements in human history is very humbling. For this portrait I ordered the moon globe from Amazon just two days before and wasn’t really sure if the idea would work. I only had fifteen minutes to shoot the picture as I’d manage to negotiate the use of Immersive Experiences planetarium tent (which doubled as a blackout studio) between shows at New Scientist Live. Meeting Al had a profound effect upon me with his energy and infectious enthusiasm, humour, wit and charm, the twinkle in his eyes and his willingness to share his unique experiences and stories with both young and old. This picture was the last professional portrait taken of Al and his daughter’s favourite picture of her father. Every picture is a legacy not just for me but for those I photograph.”

Creativity is in Clive’s blood and while he may struggle after a shoot, you know that he will approach the next shoot with the same passion as he does every project. Whether that is shooting an international campaign, a personal project or a project educating a group of children, you will always get 100% Clive, and this is why brands and organisations want to work with him again and again. This passion and commitment, like everything comes at a cost and that cost is the post-performance depression but given the hugely positive impact that Clive has every time he starts a project, I hope that he feels that this price is worth paying, because he has such a positive impact on everyone involved directly and indirectly every time that he picks up his camera.

Clive Booth at home

“There is one last link that I feel says more about my career than any other and that’s the film I made during Covid here…”

There is still much of Clive’s journey to tell, and we are working on a part 2 which will be released in the next few months.

Stay up to date with our latest news @eizocolour on Instagram or EIZO Creative Works on LinkedIn.

If you would like to see more from Clive Booth you can follow him on Instagram @clivebooth and check out his website clivebooth.com.

The State of Sustainability in UK IT Teams

Sustainability is front-of-mind for most of the public with 70% of people wanting to see businesses take more action on climate change.

EIZO Monitors: A Legacy of Innovation, Quality and Sustainability

Choose an EIZO monitor and do not just settle for the basic screen that normally comes as standard with the computer.

Why should I choose an EIZO monitor?

If your organisation values quality, longevity, and sustainability, you should choose an EIZO monitor.

EIZO Interviews Tigz Rice

Long-term EIZO user Tigz Rice, who has established herself as one of the leading empowerment photographers with an incredibly successful career shooting

EIZO ColorEdge PROMINENCE CG1 Product Showcase

EIZO releases 30.5-inch ColorEdge PROMINENCE CG1 true reference monitor with built-in calibration and advanced interfaces for efficient creation workflows.

EIZO FlexScan EV4340X Product Showcase

Discover EIZO's largest FlexScan EV4340X monitor with built-in USB Type-C dock for business professionals.

EIZO FlexScan EV3450XC Product Showcase

EIZO Unveils Its First Ultrawide, Curved Monitor with Built-In Webcam, Microphone, and USB Type-C Dock for Business Professionals.

EIZO Interviews Hamish Brown

Never heard of Hamish Brown? Well, that is probably not a surprise as it is not unusual for photographers work to be the cover image of the album or the front page of the book or magazine. If you have heard of Robbie Williams or Anthony Joshua and seen a picture of either of these British Icons, then it is more than likely that you would have seen some of Hamish’s work, but it is probably still one of the best photographers of which you have never heard.

UK EIZO Student Awards 2022

The EIZO Student Awards is an annual competition hosted in the UK that provides students studying photographic and filmmaking courses an opportunity to showcase their talent and develop real life experience that will hopefully give them a head start in the creative industry.

Sustainable by Design

At EIZO believe that we have a duty to do what we can to ensure the future of our planet, so everything we do is ‘Sustainable by Design’.

Small Streams Make a Mighty River

Sustainability is becoming more important to individuals and companies alike, and if we all take a few small steps, we can all move towards a more sustainable future.